No, not Enzo Bianchi the Emmerdale character nor even Enzo Bianchi the wine merchant. Father Enzo Bianchi is the Prior of a monastic community of men and women at Bose in Italy and this book is a collection of his reflections on 45 key elements of the spiritual journey. These elements include practices such as ascetism and prayer, temptations such as akedia or spiritual listlessness, virtues such as patience and faithfulness and disciplines such as fasting and poverty. The book concludes with four superb chapters reflecting on illness, old age, death and (as an epilogue) joy.

Due to the profundity of the wisdom it contains, this is definitely not a book to be read at one sitting. It is a book to be read slowly and savoured, with frequent pauses for prayer and meditation. For example, Bianchi's definition of patience- "patience is the art of living within the incompleteness and the fragmentary nature of the present moment without giving in to despair" - has proved so helpful to me that not only have I memorised it, but by dint of constant repetition, my entire family now knows it too ... Similarly, when struggling with trying to articulate which evangelistic techniques I found unacceptable, I was helped by Bianchi's reflection on conversion: "only men and women changed by the gospel, who demonstrate their conversion to others through the way they live, are also able to request conversion of others." As a novice on the path of contemplative prayer, I appreciated his definition of a contemplative as "an expert in the art of discerning God's presence." Thus Bianchi sees even prayers of request as being in essence contemplative, because in requesting something from God "we place a certain distance between ourselves and our situation, establish a period of waiting between our need and its satisfaction, and try to make space for an Other within the enigmatic situation in which we are living."

Bianchi's wisdom is not restricted to helping individuals on their personal journey, for he often reflects on issues which affect the whole church. Thus in his thoughts about hope he challenges the church to open up vistas of meaning for the world, "to give hope and the possibility of a future to concrete, personal lives, and show that it is worth living and dying for Christ." For Bianchi, Christians communicate their hope "by living according to the logic of the Paschal event" which is the logic that allows Christians to live in community with people they did not choose, and even makes it possible for them to love those who hate them. Bianchi then goes on to discuss the nature of forgiveness, which he defines as "the mysterious maturity of faith and love that allows us, when we have been offended, to choose freely to renounce our own rights in a relationship with someone who has already trampled on our rights ... an enemy is our greatest teacher, because he or she unveils what is in our heart but does not emerge when we are on good terms with others." This leads Bianchi on to consider humility, which, he concludes, is above all humiliation - the place where we are led to discover who we are through the actions of others, of life and of God. Bianchi has a Trinitarian understanding of the Christian communion which demands both that the church cannot reject responsibility for others, but also that "a horizontal principle of attentiveness to the other" is insufficient as it runs the risk of exclusivity or rivalry. 'The other' is not enough - the transcendent 'Third' is also needed, and thus Bianchi concurs fully with Barth's statement that "the Church is the continually renewed communion of men and women who listen to and give witness to the Word of God."

Finally, Bianchi also addresses issues of importance to humanity as a whole. In his trilogy of chapters on illness, aging and death, Bianchi offers some perspectives which were quite new to me. For instance, he suggests that illness "is a new point of view from which to look at reality", one which strips us of our illusions about life. Illness shatters some of the meanings which we have carefully constructed and calls us to accept responsibility for assigning a meaning to our suffering. Thus he offers the important pastoral perspective that ill people should be the teachers of those who sit at their bedsides. When considering aging, he once again quotes Barth: "old age offers itself to men and women as an extraordinary possibility to see life not as duty, but as grace." Old age is another time of meaning-making, of looking back at one's life and attempting to discern the hidden narrative, the golden thread, and this is why it is so important for older people to tell and re-tell their stories. Finally life must be handed over in death, but Bianchi has an unusual perspective on death also. For him, prayer is a preparation for death, for in setting aside time to pray, we give our time over to God, and time is life. Death, and particularly the fear of death, remain the enemy whom we battle in Christ "because so many of the strategies we use in an attempt to escape the anxiety of death follow the logic of idolatry and sin." Bianchi concludes by considering joy - "joy reveals itself in our discovery that we are satisfied."

This is a wonderful book, ideally suited for using in daily devotions as the chapters are short but very profound. You can buy it from Amazon here or order it from the Pontypridd Harvest Christian Bookshop here.

Rosa's Readings

Tuesday, 21 May 2013

Saturday, 18 May 2013

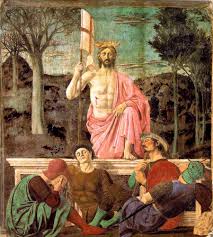

Resurrection: Borgo San Sepolcro - Rowan Williams

To celebrate Pentecost, here is another of Williams' poems. This one reflects on Piero della Francesca's fifteenth century depiction of the resurrection:

According to Ben Myers, Aldous Huxley called this the greatest picture in the world. I think that this is the greatest reflection on the resurrection I have ever read:

According to Ben Myers, Aldous Huxley called this the greatest picture in the world. I think that this is the greatest reflection on the resurrection I have ever read:

I have been defeated by the push, the green implacable rising: praise God!

Rowan Williams Headwaters can be ordered from Harvest Bookshop (and elsewhere!) here.

Today it is time. Warm enough, finally,

to ease the lids apart, the wax lips of a breaking bud

defeated by the steady push, hour after hour,

opening to show wet and dark, a tongue exploring,

an eye shrinking against the dawn. Light

like a fishing line draws its catch straight up,

then slackens for a second. The flat foot drops,

the shoulders sag. Here is the world again, well-known,

the dawn greeted in snoring dreams of a familiar

winter everyone prefers. So the black eyes

fixed half-open, start to search, ravenous,

imperative, they look for pits, for hollows where

their flood can be decanted, look

for rooms ready for commandeering, ready

to be defeated by the push, the green implacable

rising. So he pauses, gathering the strength

in his flat foot, as the perspective buckles under him,

and the dreamers lean dangerously inwards. Contained,

exhausted, hungry, death running off his limbs like drops

from a shower, gathering himself. We wait,

paralysed as if in dreams, for his spring.

I have been defeated by the push, the green implacable rising: praise God!

Rowan Williams Headwaters can be ordered from Harvest Bookshop (and elsewhere!) here.

Friday, 10 May 2013

"Penrhys" by Rowan Williams

Here is Williams' poem about Penrhys, a council estate in the Rhondda which has been transformed by the constant, faithful love of a community of Christians right at their heart. I visited the estate with a group of Baptist ministers recently and was both humbled and inspired...

I love the way that Williams draws a comparison between the teenage Mary in the statue in the shrine, and the teenage mothers at the bus stop. Commenting on the poem, Benjamin Myers writes: "that is what incarnation looks like. Christ is defamiliarised when we perceive him like this, with a grittiness untouched by religious disinfectant.":

Penrhys

The ground falls sharply; into the broken glass,

into the wasted mines, and turds are floating

in the well. Refuse.

May; but the wet, slapping wind is native here,

not fond of holidays. A dour council cleaner,

it lifts discarded

Cartons and condoms and a few stray sheets

of newspaper that the wind sticks

across his face -

The worn sub-Gothic infant, hanging awkwardly

around, glued to a thin mother,

Angelus Novus:

Backing into the granite future, wings spread,

head shaking at the recorded day,

no, he says, refuse,

Not here. Still, the wind drops sharply.

Thin teenage mothers by the bus stop

shake wet hair,

Light cigarettes. One day my bus will come, says one;

they laugh. More use'n a bloody prince,

says someone else.

The news slips to the ground, the stone dries off,

smoke and steam drift uphill

and tentatively

Finger the leisure centre's tense walls and stairs.

The babies cry under the sun,

they and the thin girls

Comparing notes, silently, on shared

unwritten stories of the bloody stubbornness

of getting someone born.

I love the way that Williams draws a comparison between the teenage Mary in the statue in the shrine, and the teenage mothers at the bus stop. Commenting on the poem, Benjamin Myers writes: "that is what incarnation looks like. Christ is defamiliarised when we perceive him like this, with a grittiness untouched by religious disinfectant.":

Penrhys

The ground falls sharply; into the broken glass,

into the wasted mines, and turds are floating

in the well. Refuse.

May; but the wet, slapping wind is native here,

not fond of holidays. A dour council cleaner,

it lifts discarded

Cartons and condoms and a few stray sheets

of newspaper that the wind sticks

across his face -

The worn sub-Gothic infant, hanging awkwardly

around, glued to a thin mother,

Angelus Novus:

Backing into the granite future, wings spread,

head shaking at the recorded day,

no, he says, refuse,

Not here. Still, the wind drops sharply.

Thin teenage mothers by the bus stop

shake wet hair,

Light cigarettes. One day my bus will come, says one;

they laugh. More use'n a bloody prince,

says someone else.

The news slips to the ground, the stone dries off,

smoke and steam drift uphill

and tentatively

Finger the leisure centre's tense walls and stairs.

The babies cry under the sun,

they and the thin girls

Comparing notes, silently, on shared

unwritten stories of the bloody stubbornness

of getting someone born.

Thursday, 9 May 2013

J.K. Rowling: "The Casual Vacancy"

I only bought this book because my book club were reading it, and I nearly didn't get past the first fifty pages because I thought that it was unnecessarily obsessed with sex. I wondered initially whether Rowling had made a deliberate effort to distance herself from Harry Potter and to mark herself out as an 'adult' writer. but as I progressed with the book I decided that I had misjudged her. Rowling is painting a picture of an obsessive society. The book opens with the sudden death of Barry Fairbrother, a man in his forties who also happened to be a local councillor in a divided community. Old Pagford is obsessed with success, money and beauty. The layout of local council boundaries means that the children from the local council estate can attend the beautiful little primary school, and that the council is responsible for the addiction clinic which struggles to meet the needs of the drug addicts from the estate. But now there is a chance for the boundaries to be re-drawn, and for the council estate to fall out of Pagford's remit. This would mean that the clinic would close and that the council estate children with their dirty clothes and foul language would no longer attend the picturesque little school. Barry Fairbrother had been spearheading a campaign to keep things as they were - but Barry is dead. Who will step into his shoes on the local council, and who will fight for the rights of the council estate residents now?

One by one, each of the families we meet in the opening chapters of the novel puts forward a candidate to fill Barry's seat on the council. One by one, the teenagers in each family attempt to wreck their parents' chances of success by revealing the tensions and secrets hidden at the heart of their family lives.

This is a brilliantly observed and deeply sympathetic book. It sympathises with the teenage craving for authenticity and honesty as well as the desperate craving for another shot of youth and health and attractiveness experienced by the aging woman. It sympathises with those trapped in the vicious cycle of drugs, poverty, abuse and violence on the council estate, as well as those trapped by mental illness and alcoholism in the genteel surroundings of Old Pagford. (Interestingly, I didn't think that it was terribly sympathetic to men: in general, the female characters were stronger, better developed and far more mature.) It paints a very interesting picture of how power is sustained and exercised in small communities, and I think that anyone who sits on any committee should read it ....

One by one, each of the families we meet in the opening chapters of the novel puts forward a candidate to fill Barry's seat on the council. One by one, the teenagers in each family attempt to wreck their parents' chances of success by revealing the tensions and secrets hidden at the heart of their family lives.

This is a brilliantly observed and deeply sympathetic book. It sympathises with the teenage craving for authenticity and honesty as well as the desperate craving for another shot of youth and health and attractiveness experienced by the aging woman. It sympathises with those trapped in the vicious cycle of drugs, poverty, abuse and violence on the council estate, as well as those trapped by mental illness and alcoholism in the genteel surroundings of Old Pagford. (Interestingly, I didn't think that it was terribly sympathetic to men: in general, the female characters were stronger, better developed and far more mature.) It paints a very interesting picture of how power is sustained and exercised in small communities, and I think that anyone who sits on any committee should read it ....

Benjamin Myers: "Christ the Stranger: the theology of Rowan Williams"

Nah ist Und schwer zu fassen der Gott - the god is near and hard to grasp. Benjamin Myers uses this Holderlin quote to open his exhilarating account of Rowan Williams' theology. Myers sees three main periods in Williams' thought. The first extends from Williams' undergraduate days to the late 1980s, and this is characterised as being dominated by Wittgenstein and the question of the relation between language and sociality. During this period Williams entered the world of Russian Orthodoxy and completed his doctoral thesis on Vladimir Lossky's apophatic theology. For Lossky, personhood is a kenotic reality, echoing the "enormous movement of painful, ecstatic self-renunciation" which constitutes the Trinity. As Myers puts it, "we are most human when we are cracked, when each self bleeds out into the lives of others." Also during this period, Williams' exposure to the thought of Donald MacKinnon and his study of T.S. Eliot led him to develop what Myers terms his "tragic moral vision". Williams' refusal to accept the consolation of fantasy, and his deep suspicion of the human tendency for self-delusion, lead him to argue that to act morally is to act against the grain of the world, even when our actions are tragically doomed or limited, even when our actions seem to go against what is humanly possible. Every act is enmeshed in a web of tragic relations and therefore cannot be unambiguously good. And yet act we must, for God is at work in this damaged world, and so must we be. The event which begins the Christian tradition is the resurrection, an event of rupture which shatters our language and cannot be captured by our narrative. For Williams, Jesus is the fullness of divine meaning in one human life whose weight buckles the structures of human language. God is unutterably strange, not because He is so far away, but because in Christ He has come unbearably near. The cross is God's own negative theology, destroying our human capacity to make and share meaning, until our language itself is baptised and renewed. For Williams, "the Christian tradition as a whole ... is this continuing process of the conversion of human language to God."

From the late 1980s to the late 1990s, Williams entered into a dialogue with Hegelian thought in order to address the realtionship between identity and difference. In 1992 Williams was consecrated Bishop of Monmouth and his theology of Christ as the head of a reconciled human community was challenged by the palpable and seemingly irreconcilable differences within the church. He engaged with the work of Gillian Rose, who was arguing that both the teleological approach (in which difference is eliminated through synthesis) and the postmodern ethical theory of the Other are inadequate. Instead of attempting to seek resolution we should work at sustaining the broken middle, the 'agon' of difference "where we endure the anxiety of difference without seeking the relief of synthesis". Williams developed Rose's work into a Christian theology of identity in which all social life is interpreted as kenosis - a willingness to endure difference and a resistance of the desire to achieve synthesis. However, this is not a passive position but involves continual movement towards the other and continual work in order to achieve growth. Thus the church will be a community marked by a patient struggle sustained by the Holy Spirit.

Williams became Archbishop of Canterbury in 2002 and since then has devoted much attention to the Christian doctrine of God. Myers presents a picture of Williams' trinitarian vision which I found deeply compelling. Augustine had famously distinguished between frui (enjoyment: choosing something for its own sake alone) and uti (use: choosing something for the sake of a higher goal.) For Augustine, only God can be enjoyed in this sense: to try to enjoy worldly objects as "the end and sum of our joy" is to consume them, to exclude them from possessing any other meaning other than the satisfaction of our own desire. Williams developed this Augustinian concept of desire into a doctrine of the trinity. God is an infinite ground of objectivity and love, and within the love of God itself there opens up a differentiation: God loves God. This desire cannot be gratified by the other partner, and so the excess of love for the other is deflected into a Third: the Spirit, who "sustains the exchange between Father and Son precisely by being more than that exchange, by personifying their mutual excess of love ... In short, God is a trinity of love: the lover, the beloved, and a constantly expanding surplus of love itself."

Perhaps this brief and inadequate summary conveys the impression that this is a dry and academic book. Nothing could be further from the truth. There are frequent interludes presenting and discussing Williams' poetry, often in relation to the icons which have played an important part in his spirituality. I was particularly moved by the presentation of Williams' poem on the Penrhys estate, which I have visited recently with other Baptist ministers from South Wales. The embedding of a discussion of Rublev's trinitarian icon within the exposition of Williams' doctrine of the trinity allowed me to build a bridge between the abstract theology and my daily, messy spirituality where I turn up, scruffy and unlovable, to prayer and find that God has saved me a seat at His table and is looking at me with love. Indeed, this is what I most loved about this book. It is a portrait of a brilliant yet humble man who constantly works away at the inevitable tensions between his intellectual life, his spiritual journey and his practical ministry. He gives me hope that my discipleship is both indispensable in practice and intellectually tenable. Moreover, Benjamin Myers writes in an engaging and inspirational style. I would recommend this book to all who like thinking and ideas, and who are convinced that Jesus offers a real hope in our often tragic world.

You can buy this book at Amazon here but why not support a small local bookshop and order it from Harvest Bookshop here?

From the late 1980s to the late 1990s, Williams entered into a dialogue with Hegelian thought in order to address the realtionship between identity and difference. In 1992 Williams was consecrated Bishop of Monmouth and his theology of Christ as the head of a reconciled human community was challenged by the palpable and seemingly irreconcilable differences within the church. He engaged with the work of Gillian Rose, who was arguing that both the teleological approach (in which difference is eliminated through synthesis) and the postmodern ethical theory of the Other are inadequate. Instead of attempting to seek resolution we should work at sustaining the broken middle, the 'agon' of difference "where we endure the anxiety of difference without seeking the relief of synthesis". Williams developed Rose's work into a Christian theology of identity in which all social life is interpreted as kenosis - a willingness to endure difference and a resistance of the desire to achieve synthesis. However, this is not a passive position but involves continual movement towards the other and continual work in order to achieve growth. Thus the church will be a community marked by a patient struggle sustained by the Holy Spirit.

Williams became Archbishop of Canterbury in 2002 and since then has devoted much attention to the Christian doctrine of God. Myers presents a picture of Williams' trinitarian vision which I found deeply compelling. Augustine had famously distinguished between frui (enjoyment: choosing something for its own sake alone) and uti (use: choosing something for the sake of a higher goal.) For Augustine, only God can be enjoyed in this sense: to try to enjoy worldly objects as "the end and sum of our joy" is to consume them, to exclude them from possessing any other meaning other than the satisfaction of our own desire. Williams developed this Augustinian concept of desire into a doctrine of the trinity. God is an infinite ground of objectivity and love, and within the love of God itself there opens up a differentiation: God loves God. This desire cannot be gratified by the other partner, and so the excess of love for the other is deflected into a Third: the Spirit, who "sustains the exchange between Father and Son precisely by being more than that exchange, by personifying their mutual excess of love ... In short, God is a trinity of love: the lover, the beloved, and a constantly expanding surplus of love itself."

Perhaps this brief and inadequate summary conveys the impression that this is a dry and academic book. Nothing could be further from the truth. There are frequent interludes presenting and discussing Williams' poetry, often in relation to the icons which have played an important part in his spirituality. I was particularly moved by the presentation of Williams' poem on the Penrhys estate, which I have visited recently with other Baptist ministers from South Wales. The embedding of a discussion of Rublev's trinitarian icon within the exposition of Williams' doctrine of the trinity allowed me to build a bridge between the abstract theology and my daily, messy spirituality where I turn up, scruffy and unlovable, to prayer and find that God has saved me a seat at His table and is looking at me with love. Indeed, this is what I most loved about this book. It is a portrait of a brilliant yet humble man who constantly works away at the inevitable tensions between his intellectual life, his spiritual journey and his practical ministry. He gives me hope that my discipleship is both indispensable in practice and intellectually tenable. Moreover, Benjamin Myers writes in an engaging and inspirational style. I would recommend this book to all who like thinking and ideas, and who are convinced that Jesus offers a real hope in our often tragic world.

You can buy this book at Amazon here but why not support a small local bookshop and order it from Harvest Bookshop here?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)